Challenges and opportunities with disruptive innovations

Tricky forces emerge within a company when things suddenly stop going as expected. That’s when there is a need for someone who can assess the situation objectively, without being influenced by internal pressures.

It is not easy for an established company to deal with market disruptions, likewise it’s not easy for a new company to disrupt the market. Throughout my career, I’ve seen both go wrong multiple times, leading to serious challenges for the companies involved—some of which they never recovered from.

It is not easy for an established company to deal with market disruptions, likewise it’s not easy for a new company to disrupt the market. Throughout my career, I’ve seen both go wrong multiple times, leading to serious challenges for the companies involved—some of which they never recovered from.

That could have been avoided if they had focused less on the urgency of the moment and more on the bigger picture. Admittedly, that’s not easy to do in the heat of the moment. When things suddenly stop going as expected, tricky forces emerge within a company. That is when you need someone who can look at the situation objectively, without the internal pressures clouding their judgment.

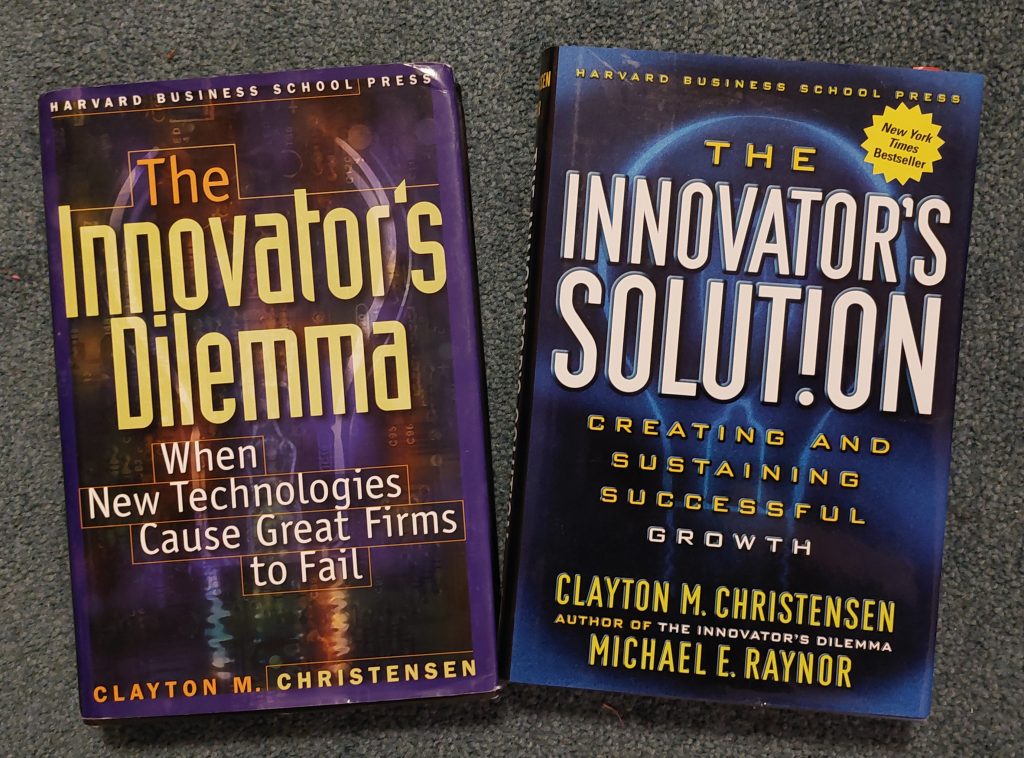

Some of the actions required in such situations seem logical to me, but they’re not (always) obvious to the CEOs of medium and large companies. There is research on this topic, documented in accessible books—like The Innovator’s Dilemma & The Innovator’s Solution by Christensen.

I have had both books on my shelf for decades. I still frequently reference The Innovator’s Dilemma to explain why focusing 100% on existing customers can be fatal for a business (as I have also discussed in a previous blog). In short: when a disruptive innovation first appears, it is initially irrelevant to the existing market because large customers demand features the innovation can not yet deliver (for example, price per bit on a hard disk). However, new customers value different aspects of the innovation (cheaper and smaller hard disks, where total storage capacity isn’t the primary concern). Eventually, there comes a moment when the new type of hard disk also achieves a lower price per bit. At that point, the older generation of companies suddenly faces an existential crisis.

I did not have The Innovator’s Solution as much top of mind, so I recently flipped through it, only to realize I had already internalized that knowledge—I had become unconsciously competent.

This book picks up where The Innovator’s Dilemma leaves off: once a disruptive innovation enters the market, how does an existing company defend itself against disruption? On the flip side, how does a new company bring a (potentially) disruptive product to market in a way that prevents existing players from crushing it immediately?

The latter is, of course, my core business: staying relevant in a shifting technological landscape and, consequently, an evolving business world.

No matter which side you’re on, if your current customers are not interested in your new product, you need to find new customers. That sounds obvious, but your existing sales and marketing teams likely ik not be of much use here as they are good at their jobs precisely because they know how to sell to your current customers and target audience! The same applies to your middle management; they are focused on maximizing profits from your existing customer base. In fact, that is probably embedded in their annual objectives.

Before you can pivot, you need to explicitly adjust those annual goals. Otherwise, people will continue to act based on what they’ve been promised bonuses and promotions for. This is less obvious than you might think. I once worked at a company where the leadership “forgot” this detail when they decided to drastically change direction mid-year and were surprised when the company didn’t follow…

You need people who can attract customers that are not yet on the radar for your existing products. Perhaps they would be interested in a product that’s too simple for your current target audience. Or maybe you can reach customers who find your current offerings too expensive or complex. You will probably need a different approach to reach them. These new customers will not be at the trade shows where you currently find your clients—you may need to reach them through entirely different channels, like radio advertising. You have to entice these new customers by demonstrating how your product solves their problem, rather than trying to convince them to change their behavior to fit your product.

You will also need to make changes on the production side. Suppose your technical team is used to building products designed to last 35 years, as Lucent Technologies did back when there was still a market for large telephone exchanges. They built their products to be incredibly robust.

But what if your new market expects products to be written off in just three years (like computers)? In that case, your internal quality standards are too high, making your new products too expensive for the target market!

The same applies at the other end of the spectrum. If you are not targeting budget-conscious non-customers but instead aiming for exclusive, high-end customers willing to pay a premium for personalized service, then you need to flip everything I just said 180 degrees. You will need the highest quality, maximum customization to meet customer demands, and a willingness to invest more in both cost and delivery time.

All of this sounds completely logical, yet few companies consider these factors when they’re in the middle of a crisis—when deadlines and profit targets narrow their perspective.

That is exactly when you should take a step back and analyze what your real challenge is before making adjustments.

Tip: If the change is too big, create a new division that reports directly to top management and has its own (profit) objectives. “Loan” the right employees to this new division so they can figure out how the new market works. Do not assume that your new product follows the same rules as your old one—give your team the space to discover where the real opportunities lie.

And of course, if you see these kinds of challenges in your market and want to brainstorm about them, feel free to reach out. The first hour is free anyway.